Authors: Mike Caulfield, Kayla Duskin, Stephen Prochaska, Scott Philips Johnson, Annie Denton, Zarine Kharazian, and Kate Starbird

University of Washington

Center for an Informed Public

The following analysis from researchers at the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public (CIP) examines emerging online narratives involving “ballot trafficking” ahead of the release of the documentary 2000 Mules, which, according to its film trailer, will feature videos of people engaging in suspicious activity around ballot drop boxes, presented within a “trafficking” frame. According to the publisher description of Dinesh D’Souza’s related book, D’Souza will present evidence that “The 2020 presidential election was rife with fraud orchestrated by the Democratic Party,” where “ballot mules” took ballots and dumped those ballots in collection boxes throughout a voting district.

Regardless of the veracity of the upcoming film’s claims, they can be seen in the context of a grander narrative — alleging a highly coordinated election fraud campaign of a scale that would have impacted the result of the 2020 election. The CIP has tracked related claims before in work with the Election Integrity Partnership (EIP), documenting hundreds of false, misleading, exaggerated and/or unsubstantiated claims about the 2020 election that functioned to sow doubt in election procedures and election results. D’Souza participated in the propagation of several of these — previously offering different explanations for the mechanism of alleged election fraud. This includes relaying speculation that Sharpie pens may have been causing the disenfranchisement of voters in Arizona and repeatedly retweeting claims that large numbers of dead people had voted. And though the central claims in “2000 Mules” are new, they are perhaps not surprising — our own research team predicted as early as October 2020 that election fraud narratives would develop around “videos claiming to show issues around ballot dropboxes, such as voters dropping off more votes than allowed, or security being mishandled.”

Here, we explain how the rhetoric around “ballot trafficking” — an antecedent of the “ballot mules” claim — encompasses a potentially misleading framing of ballot collection violations and invites confusion of the ultimate impact of such violations. And we document how this term took shape and spread online in the months leading up to the release of D’Souza’s film.

Background

Ballot collection is a practice whereby a person who is not the voter transports a ballot to a voting location. Restrictions as to who this person may be apply in many states, with some states only allowing family members and caregivers to return ballots. Some level of ballot collection is allowed (or not expressly prohibited) in all states except Alabama. [1]

In states where third parties may return votes for the voter, the practice of collecting ballots in this manner has been referred to pejoratively as “ballot harvesting,” a term which implies a level of mechanistic manipulation. Campaigns to restrict ballot collection are necessarily contentious. Ballot collection is relied on by many, including those on tribal lands and those who are ill or disabled, and has been part of general voter engagement strategies in a number of rural and urban centers. To restrict collection is to potentially disenfranchise some set of voters, and such impacts are not felt equally. At the same time, introducing any individual between the voter and the ballot box entails risk. [2]

While there is much to be said about illegal ballot collection claims and narratives, this article focuses on a more limited issue: the rise of a new, arguably deceptive, and inflammatory frame for the practice: “ballot trafficking.” We detail the emergence of this term, look at its path to prominence, and examine its current level and locus of use. We also consider implications of the associated framing for election workers, journalists, and policy makers, and make some preliminary recommendations.

“Trafficking” and “mules” as deceptive terms

The use of loaded or euphemistic terms can mislead the public. While the line between “mere spin” and deceptive language is a fuzzy one, some terms can create distinctly false impressions about the events they claim to describe.

The terms “ballot trafficking” and “ballot mules” potentially distort the public’s understanding of the electoral process in two key ways:

- The status of the ballot: The terms imply the ballots themselves are, by association, invalid or illegal.

- The associations of the terms: The terms are potentially inflammatory, and connect to terms popular in conspiracy theory communities.

On the first count, the term trafficking is usually defined as the dealing or trading of something illegal. The long-standing term “vote trafficking,” for example, has been used in the past to describe systems of buying votes from voters. In these cases, the voter’s involvement in fraud renders the vote invalid. This parallels other uses of the term, where traffickers buy and sell illegal items or engage in illegal trade.

Illegal ballot collection, on the other hand, does not usually involve illegal votes. In fact, the regulations around ballot collection are there to protect the legal votes that are collected from interference by a third party. This distinction is particularly important, because unless it can be shown that the third-party collector modified the ballots, findings are unlikely to cast doubt on previous voting tallies.

The term “ballot mules,” which is increasingly popular in some circles, similarly calls up parallels to the term “drug mules,” where individuals smuggle illegal drugs across borders. But again, the parallel is erroneous. If a person takes a ride with a cab that turns out not to be properly licensed by the city, the cabbie is not now a “passenger mule” and the passenger is not being “trafficked” — the passenger is simply a passenger in an illegal cab. Likewise, as Secretary of State Brad Raffensberger has emphasized in Georgia, while those engaged in illegal ballot collection will be punished, the votes that were cast are presumed valid and the people who cast them are not under sanction.

It’s possible, of course, that there may be future revelations, but the term as currently applied — and gaining steam through motivated amplification — can be misleading. There is a substantial difference between something being illegally transported and something illegal being transported, and eliding this difference is likely to confuse the public.

A final note is that these terms are also inflammatory. The terms overlap both with the sex-trafficking fixations of numerous conspiracy theory communities and invoke highly racialized tropes around drug smuggling. They assume — rather than prove — a large and shadowy criminal conspiracy, and potentially put legal collectors at personal risk.

Spread and adoption of “ballot trafficking” language

With the use of the term “ballot trafficking” to describe ballot collection recently becoming widespread on Twitter, it may be tempting to see the term’s adoption as a grassroots phenomenon. We did not find that to be the case. Investigating the use of the term on Twitter over the past two years, we find that while recent activity around the term may appear organic, the term itself was propelled to prominence by a mix of elite messaging, think tank promotion, and advocacy group communications.

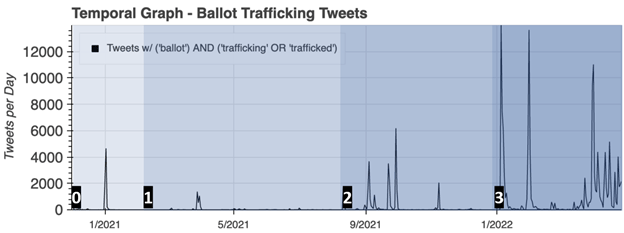

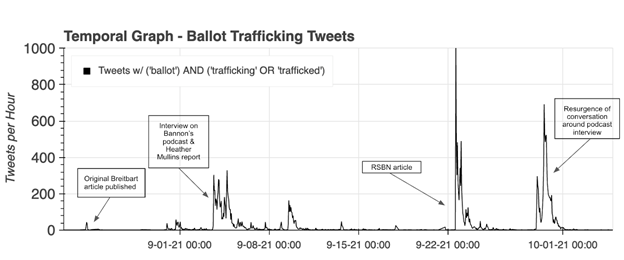

Data and Methods. To understand how this term, and the frame around it, was seeded and spread, we can look to the social media record. Our team applies a grounded, interpretative mixed-method approach to the investigation of how rumors and other narratives originate and propagate online. We often turn to Twitter, where the data is public and available for research, to get a sense for how a story was spreading online, applying a grounded (Charmaz, 2014), interpretative, mixed-method approach for understanding how content is seeded and spread (e.g., see Starbird et al., 2014, Maddock et al., 2015, and Wilson et al., 2018). We also search other publicly available data from other platforms and trace content from tweets to other platforms. Here, we focus on a real-time collection of tweets related to ballots, votes, and voting, and we scope that collection to tweets that contain both “ballot” and a trafficking related term (“trafficking,” “trafficked,” “trafficker”). We then remove noise by eliminating tweets referencing other discourses around trafficking (e.g., tweets with “human” or “drug”). The temporal graph below (Figure 1) shows the volume of “ballot trafficking” tweets per day between December 2020 and April 2022. This Twitter data is the primary source for the analysis presented here.

Figure 1: A temporal graph showing the volume of tweets per day with “ballot trafficking” or a related term. The numbers map to the phases described below.

Analysis: Actors and Domains.

Figure 1 reveals how the “ballot trafficking” term grew in use over time, initially appearing as short bursts of activity and then more recently picking up as sustained discussion. (This graph focuses on Twitter, but similar trends can be seen on other platforms.) We return to this graph and talk about the conversation’s development across different phases below, but first, to better understand who was participating in this spread, we also created an interactive cumulative tweet graph for the same time period.

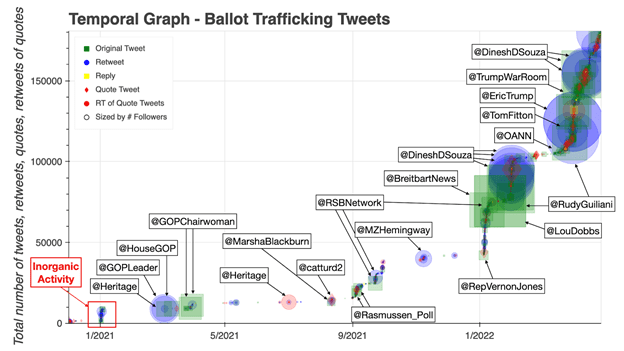

Figure 2: Cumulative uses of ballot trafficking language in tweets, retweets, and replies. Each shape is a tweet with a “ballot trafficking” term, sized relative to the number of followers of the account. Only accounts with very high follower counts appear in the graph. For example, the @GOPLeader account has more than 1M followers. However, smaller accounts do contribute to rise along the y axis. An interactive version of this graph is available here: http://faculty.washington.edu/kstarbi/BallotTrafficking_Total.html

This cumulative graph shows how high-follower accounts from GOP leaders, conservative activist organizations, and right wing media outlets and pundits, participated in — and in many cases helped to seed and/or catalyze — the spread of “ballot trafficking” claims. Early use of the term (March 2021) by high-profile Republican political figures and conservative organizations gained traction in right wing media in September 2021 as it was tied to a series of allegations in Georgia and Arizona. Subsequent allegations and evidence, as well as the promotion of an associated documentary, drove it into broader usage by high-follower accounts in January 2022, a trend that has continued to the present (April 30, 2022).

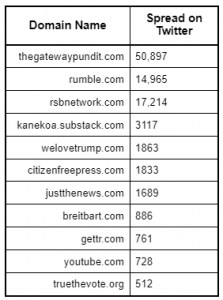

Examining the most-cited websites in this discourse can be valuable for understanding how the language and framing around ‘ballot trafficking’ developed and spread.

Table 1: Top 10 most-cited domains in ‘ballot trafficking’ tweets (Dec 2020 – April 2022)

Table 1 lists the most prominent domains (websites) in the Twitter discourse around ballot trafficking. The list features several hyperpartisan, online-first media outlets that are aligned with conservative and/or pro-Trump political views. In particular, the Gateway Pundit — a hyperpartisan online news outlet that was perhaps the most influential “repeat spreader” of misleading claims about the 2020 election — was the most cited domain in this discourse, with 50K tweets linking to many different articles. True the Vote (truethevote.org), a conservative organization whose stated mission is to stop voter fraud, appears at #10 on this list.

Taken together, our analysis of the actors and domains that were most influential in this discourse suggests that the ‘ballot trafficking’ narrative took shape through a concerted — though not necessarily coordinated — effort by right-wing media outlets, GOP political figures, and conservative activist organizations.

Temporal Analysis

Through our analysis, we noted four distinct phases (thus far) in the development and spread of the “ballot trafficking” term and framing:

- 0. Activity around different uses of the term, not related to ballot collection.

- 1. An early, partisan, elite-driven phase where the term was used to frame general public debates about election law around ballot collection. (Spring/Summer 2021)

- 2. A frame-setting phase where the term was spread in conjunction with specific allegations about alleged evidence of events in swing states. (Fall 2021)

- 3. A broad dissemination phase where additional evidence, controversy, and institutional reaction to the events associated with the phrase in Phase 2 propelled the term into broad use, and fueled dissemination by high-follower accounts. (January 2022 – Now)

These phases map to the numbers on the graph in Figure 1.

Much early use of the term “ballot trafficking” was associated with partisan elites

(Phase 1)

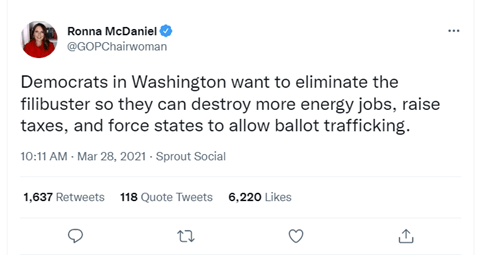

Though there is little use of the exact phrase “ballot trafficking” prior to 2021, some early associated framing appeared in an April 2020 op-ed authored by Republican National Committee Chair Ronna McDaniel. The piece used the phrase “traffic in ballots,” specifically claiming Democrats were “using ‘social distancing’ as an excuse to allow campaign operatives” to engage in the process, and mentioning attempts to loosen ballot collection regulations. The phrase was also used in a mildly popular tweet from the @GOP Twitter account promoting the piece.

In early 2021, the full term began appearing in media publications and on social media, in contexts predominantly centered around national legislation and court cases. A February 2021 opinion piece published in The Wall Street Journal on House Resolution 1 referenced existing Florida “bans [on] organized ballot trafficking.” The article was co-authored by the head of conservative advocacy group the Honest Elections Project, a group described by The Guardian as a “dark money group” fighting to restrict voting access. In March, there were a handful of social media references to ballot trafficking, including a tweet from Chuck DeVore, vice president of the conservative think tank the Texas Public Policy Foundation. Devore stated “Chief Justice John Roberts in his questions pointed out that ballot harvesting (AKA ballot trafficking), which is banned in many states…,” in reference to an Arizona voting rights case heard by the Supreme Court. Ronna McDaniel also returned to the term on her @GOPChairwoman account in a comment proposing filibuster changes:

@GOPChairwoman tweet: https://twitter.com/GOPChairwoman/status/1376220425177419787

Attaching the term to specific allegations aided broader adoption (Phase 2)

Later that year, right-wing media outlets published a series of articles with specific allegations of “ballot trafficking” — primarily based on an investigation by True the Vote, a conservative organization that has been making election fraud claims for over a decade. [3] On Aug. 24, 2021, Breitbart released an article discussing the contents of a document from True the Vote, describing the use of cell phone “ping” data to track individuals near ballot dropboxes and the acquisition of video surveillance footage of ballot drop boxes in Georgia. On the basis of that data they made a claim that 242 people were suspected of illegal ballot collection in Georgia, and described this activity as being executed by “ballot traffickers”:

“From this we have thus far developed precise patterns of life for 242 suspected ballot traffickers in Georgia and 202 traffickers in Arizona,” True The Vote’s document says. “According to the data, each trafficker went to an average of 23 ballot dropboxes.”

Figure 3 shows the timeline of Twitter activity between mid-August (around the time of the first publication of the True the Vote documents) and early-October, showing the rate of tweets per hour referencing “ballot trafficking” and revealing several bursts of activity — each around a specific media event or set of events. The original Breitbart article received a small amount of amplification on Twitter (only some of which appears in the graph below because few of those tweets included the “ballot trafficking” term). Over the next few weeks, the story about cell phone “ping” data surfaced and resurfaced on Twitter through a series of articles, other media events, and tweets.

Figure 3: Twitter activity during Fall of 2021 (Phase 2). The first large surge in activity corresponds to the interview on Bannon’s podcast and reports by Heather Mullins. The second spike in conversation revolved around an article published by RSBN rehashing the statements made by True the Vote’s president. Another series of tweets referencing the podcast interview gained popularity in late September.

True the Vote released a response article to the initial Brietbart article on Aug. 29. Afterward, a second Breitbart article was published Aug. 31 quoting True the Vote’s president’s statement in the True the Vote article that, “Ballot trafficking will soon be exposed on a massive scale.” The term “ballot trafficking” began to gain traction on Twitter shortly after that.

Tweets about these articles continued at a slow pace from Sept. 1 until Sept. 3, when there was a sharp increase due to multiple media events featuring the term, including an interview on Steve Bannon’s podcast, a report by Heather Mullins of Real America’s Voice, and a Gateway Pundit article. Additionally, links to The Kate Awakening podcast, a variety of smaller sites (welovetrump.com, speakingaboutnews.com, citizenfreepress.com), and QAnon-associated Telegram channels reported the same story. The story talked about an “upcoming video,” “video proof,” etc. of alleged ballot trafficking that was “soon to be revealed.” This technique of building anticipation around soon-to-be-released “evidence” of malfeasance by members of an opposing political party has become a common tactic employed by political influencers on both sides of the spectrum in recent years.

Over the next few weeks, subsequent stories highlighted the cell phone ping claims and/or promoted assertions that True the Vote would be releasing additional video surveillance evidence in the future. On Sept. 22, an article published by Right Side Broadcasting Network (RSBN) referencing the True the Vote article from earlier in the month gained a large audience when it was shared by RSBN’s twitter account. A final burst of “ballot trafficking” activity at the end of September featured tweets that shared snippets of content from previous articles and/or interviews published earlier that month. After that, the conversation faded.

New varieties of alleged evidence (and institutional response to them) fueled broad dissemination (Stage 3)

In early January (2022), after a period of relative dormancy, the use of the term saw explosive growth in conjunction with a claim that True the Vote had found a whistleblower who claimed he had been paid thousands of dollars to “traffic ballots” and that True the Vote had submitted video evidence to the Georgia Secretary of State’s office.

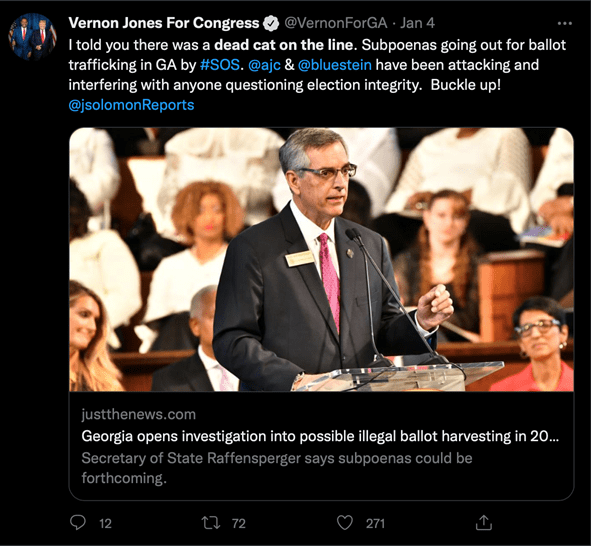

Notably, much of the early revival of the story formed around Secretary of State Raffensberger’s response to the evidence submitted. In an interview with Just the News, Raffensberger stated he would open an investigation into the claims; a move that was seen by some to legitimize the claims as well as the framing. This early tweet by Vernon Jones captured the tone of vindication present in some of the tweets, while others involve calls to pressure lawmakers.

During the same time period, Breitbart promoted a podcast (e.g., through the tweet below) that quoted True the Vote’s Catherine Engelbrecht reflecting on the new framing exhibited in the term “ballot trafficking,” suggesting an intentional shift in terminology.

Subsequent release of video of the ballot boxes, as well as promotion of the release of the documentary 2000 Mules, fueled additional spread and mainstreaming of the term. The documentary, by conservative influencer Dinesh D’Souza, is a joint production with True the Vote, which provided the research for it. Teasers for the film, promoted repeatedly throughout late winter and early spring, indicate that the film will feature videos of people allegedly breaking ballot collection law, detail the “ping evidence,” and make various election-related claims.

Given the upcoming documentary and numerous legal and legislative battles around ballot collection regulation, we expect the mainstreaming of the “trafficking” framing and related terms to continue for the foreseeable future.

Conclusion and recommendations

Initially emerging as elite-driven framing in discussions about voting rights legislation, the casting of ballot collection as “trafficking” and collectors as “mules” has gained prominence in a series of claims made about the 2020 election over the past eight months. With the impending release of 2,000 Mules and numerous state-level battles over collection regulation underway, we expect related terms and framing to continue to gain traction online. Regardless of the truth of associated claims, these terms and the underlying frame have the potential to mislead voters and increase conflict around ballot drop-off points in future elections.

Voters. Voters should check laws in their state about ballot collection, particularly if they plan to drop off a ballot for a friend or family member. A summary of current laws, organized by state, can be found on Ballotpedia. In general, a bit of preparation in deciding how and when to vote combined with a bit of research on your localities’ particular laws can go a long way. And if you find helpful information, be sure to share it with others in your area, both face-to-face and online. Healthy information environments require not only the mitigation of misinformation but the active promotion of good information.

Election workers and administrators. The use of the “trafficking” language is likely to create confusion and conflict around drop boxes in the coming election, as well as general misunderstandings about laws in individual states. These misunderstandings are likely to be magnified as national narratives collide with differences in state policy. Administrators should be prepared for videos, photos, and reports around their drop boxes to be wrongly contextualized, often through misrepresenting laws relevant to specific locales.

To prepare for such confusion, administrators are encouraged to build and promote Frequently Asked Questions pages around these issues that provide localized answers well before the election. Setting up such pages centered on specific issues is helpful in two specific ways. First, it may allow some individuals to obtain direct answers as various incidents and issues emerge. More importantly, however, such FAQ pages are part of a “help the helpers” strategy: they provide a quick, accessible resource for reporters, community leaders, and ordinary citizens to help clear up confusions as they arise, and in some cases may provide a basis for quick platform mitigation of emerging misinformation. Since every minute matters when addressing emerging misinformation, having well-vetted, well-established pages available to help others answer such questions is an important part of a rumor control strategy.

Journalists. Terms are often unintentionally normalized by coverage of their spread. As one recent example, the pejorative term “ballot harvesting” came into use first as part of a partisan messaging campaign about ballot collection regulation, but became normalized over the course of coverage, and now has become a commonly used term for the practice.

With “trafficking” language providing a potentially misleading and inflammatory frame, how should journalists treat such terms?

- Where possible, use the language used by experts or professionals to describe the behavior. In this case the professional and legal term for the practice of third parties delivering ballots is ballot collection, and is a settled enough term that even the recent Supreme Court opinion upholding state-level bans on the process refer to it as “ballot collection.”

- That said, when a term is already prevalent, it can be important to note the language others are using around the practice. When journalists ignore common terms completely it can create “data voids” – if only partisan news sites use a term, when people search on that term they will only find slanted coverage. Make sure, however, when noting the term that you explicitly note the provenance of the term, and in initial use set it off in quotation marks if your style guide allows.

For more general tips on covering misinformation, consult the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism’s Responsible Reporting Toolkit.

Additional Citations

- [1] As of this writing (April 2022). The legislative environment on this is changing rapidly, check Ballotpedia for more information: https://ballotpedia.org/Ballot_harvesting_(ballot_collection)_laws_by_state

- [2] For more discussion on these points see https://theconversation.com/is-ballot-collection-or-ballot-harvesting-good-for-democracy-we-asked-5-experts-156549

- [3] https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/10/the-ballot-cops/309085/

PHOTO AT TOP: A ballot drop-off bin in Orange County, California during the 2020 U.S. elections. Photo by Sharon Hahn Darlin via Flickr / CC BY 2.0