Through our work with the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA), we’ve found that provenance can help better calibrate trust and accuracy perceptions of media. But it can come with its own risks of misinterpretation.

By Kevin Feng, Jina Yoon, and Amy X. Zhang

University of Washington

Center for an Informed Public

The old adage “seeing is believing” can no longer be said about media on today’s internet, thanks to the rise of generative AI and the anticipated deluge of synthetic content on social media. Just days after OpenAI announced its video generation model Sora, social media users started posting videos they claimed were AI-generated but were in fact not to (comically) highlight the uncanny realism of synthetic content.

Tweet posted by Will Smith (@WillSmith2real) on February 19, 2024.

Whether it be AI-generated faces or hyper-realistic voice clones and videos, synthetic content is quickly eroding our ability to discern fact from fiction. This has far-reaching implications for society, including the potential to sway public opinion, disrupt democratic processes, and undermine trust in our everyday information networks.

Major technology leaders have recognized the urgency of this issue. Adobe and Microsoft were among the first to join the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA), a joint effort for developing an open-source standard that makes media provenance information—such as the original source and edit history—transparent to content consumers. For example, if an image was generated by AI and then cropped, consumers would be informed of those edits by looking at the image’s provenance. Content creation tools and platforms that adopt the standard can add to a piece of media’s provenance by issuing a unique cryptographic signature every time they edit or host the media. Adoption is currently underway—in early February 2024, OpenAI adopted C2PA for its DALL-E 3 image generation model, while Meta announced plans to adopt the standard for images on Facebook, Instagram, and Threads. Two days later, Google joined the C2PA steering committee with plans to integrate the standard into its products in the near future.

Provenance standards seem like a step in the right direction when it comes to increasing media transparency and limiting the spread of visual disinformation. However, in preparation for their debut on the internet, it is crucial to understand how consumers will interact with provenance information and how that information may change their perceptions of media. We partnered with the C2PA to launch a series of experiments in April 2022 to shed light on this, and found that provenance can indeed help people better calibrate trust and accuracy perceptions of media. However, we also found that it can come with its own risks of misinterpretation.

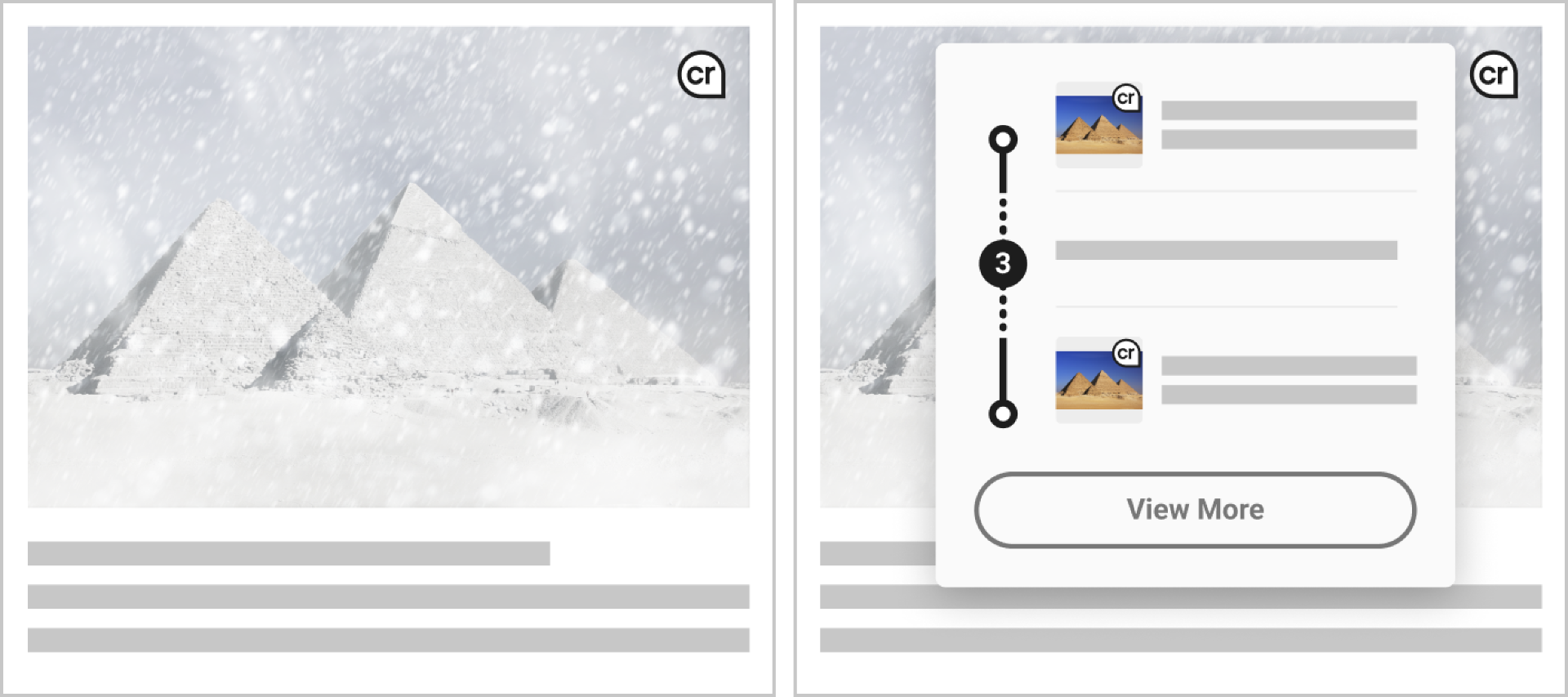

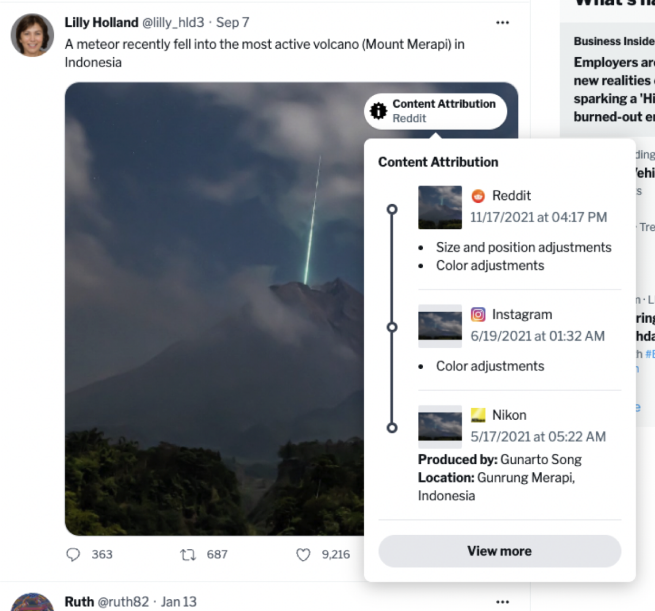

Figure 1: An example of image provenance from our study. Once the user clicks the icon on the top right corner of the image, a panel will open up revealing provenance information for that image.

We now dive deeper into our findings. First, we found that exposing social media users to provenance information had statistically significant effects on their trust and accuracy perceptions of media. For deceptive content (i.e., content that has been visually manipulated to alter the meaning of the original), participants lowered their trust and shifted their accuracy rating towards the media’s ground truth accuracy label after viewing provenance information. This meant that participants successfully identified manipulated media as less trustworthy and less accurate when provenance was disclosed. For non-deceptive content (i.e., authentic images and videos that have little to no edits), trust increased and accuracy ratings also moved closer to ground truth, but only when the provenance information was shown as verified to be accurate by C2PA.

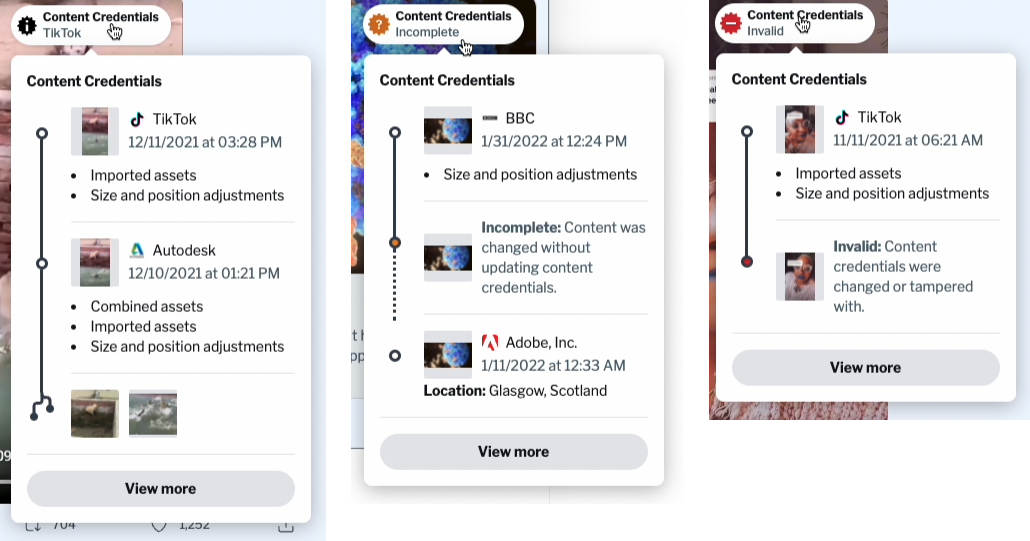

In practice, however, not all media provenance is going to be able to be verified as accurate. First, C2PA, like most standards, will roll out progressively. That means some media editing tools that haven’t implemented C2PA yet will introduce unverified edits to the provenance record. In addition, malicious actors could try to tamper with the provenance record of a piece of media, rendering the provenance information to be invalid. When we showed social media users instances of media where provenance information was missing or invalid (Figure 2), we saw that they lost trust in the piece of media. But just because the provenance isn’t verified doesn’t necessarily mean that the media itself is inauthentic, such as in the case of tools that haven’t implemented C2PA yet. Also, consider the adversarial case of a person who takes an authentic piece of media with verified provenance, purposefully adds an invalid cryptographic signature to the provenance record without changing the media’s content, and then attempts to circulate it online in order to paint the piece of media as suspicious. Thus, we argue that provenance indicators should be carefully designed to discourage users from conflating the verification of provenance to the authenticity of the piece of media itself.

Figure 2: Varying levels of provenance reliability from our study.

We also surveyed participants on their general reactions to provenance and feedback on the design of user interfaces (UIs) for displaying provenance information from the study. Participants informed us that some terminology within the UIs can be clarified, possibly with popup explainers or tooltips with more detailed definitions. For instance, they noted that the term “provenance” itself may be unfamiliar to some. Participants were overall receptive to the idea of provenance information and believed that it could help them make more informed decisions about media. At the same time, we noticed from their feedback a tendency to over-rely on provenance to prescribe a credibility judgment. Some participants suggested more clearly color coding provenance UIs so they could immediately tell when provenance is unreliable. Yet, as we warned above, just because provenance is unreliable doesn’t necessarily mean the media is too. We, along with the C2PA, believe that provenance should augment rather than replace critical thinking by offering an avenue for making more informed credibility decisions about media. Clearly communicating this goal will be pivotal as we move forward with deploying provenance standards and UIs.

Since our study, the C2PA has refined its standard and UIs, especially for disclosing the reliability of provenance information. The redesigns have been integrated into Content Credentials, a production-ready implementation of the C2PA standard, which is now available for widespread adoption by content creators and consumers. We are grateful to the C2PA for this research partnership, and are excited to see how provenance standards will be used to improve media transparency and combat online misinformation in the coming years.

You can read our full research paper, published at ACM’s Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (CSCW 2023), here.

- Kevin Feng is a third-year Ph.D. student in the University of Washington’s Department of Human Centered Design & Engineering.

- Jina Yoon is a second-year Ph.D. student in the UW Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering.

- Amy X. Zhang is an assistant professor in the Allen School and a Center for an Informed Public faculty member.

- Image at top: A synthetic image showing the pyramids at Giza surrounded by snow, with provenance indicators, via C2PA under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.